-

July

-

Margherita Hack

-

Idiom

-

Laurel and Hardy

-

Cloud computing

-

Fast food

-

Coursera

-

Tour de France

-

English modal verbs

-

Hartz concept

-

American Civil War

-

Florence

-

Rita Levi Montalcini

-

Flier (pamphlet)

-

Credit rating agency

-

Crusades

-

Web browser

-

David Bowie

-

English people

-

Cyberwarfare

-

Password

-

iOS 7

-

Massive open online course

-

Arthur Conan Doyle

-

Defense of Marriage Act

-

List of Italian musical terms used in English

-

Number

-

Unique selling proposition (USP)

-

Transatlantic Free Trade Area

-

Robin Hood

-

Louvre

|

WIKIMAG n. 8 - Luglio 2013

Massive open online course

Text is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional

terms may apply. See

Terms of

Use for details.

Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the

Wikimedia Foundation,

Inc., a non-profit organization.

Traduzione

interattiva on/off

- Togli il segno di spunta per disattivarla

A massive open online course ( MOOC) is an online

course aimed at large-scale interactive participation and

open access via the

web. In addition to traditional course materials such as

videos, readings, and problem sets, MOOCs provide interactive

user forums that help build a community for the students,

professors, and

teaching assistants (TAs). MOOCs are a recent development in

distance education. [1]

Features associated with early MOOCs, such as open licensing of

content, open structure and learning goals, and connectivism may

not be present in all MOOC projects,[2]

in particular with the 'openness' of many MOOCs being called

into question.[3]

History

Precursors

Before the

Digital Age,

distance learning appeared in the form of written

correspondence courses, broadcast courses, and early forms

of

e-learning.[5]

By the 1890s commercial and academic correspondence courses on

specialized topics such as civil service tests and

shorthand were promoted by door-to-door salesmen.[6]

Over 4 million US citizens – far more than attended traditional

colleges – were enrolled in correspondence courses by the 1920s,

covering hundreds of practical job-oriented topics, with a

completion rate under 3%.[7]

Radio was the exciting new technology of the 1920s, with

millions buying sets and tuning in. Universities quickly staked

out their wavelengths. By 1922, New York University operated its

own radio station, with plans to broadcast practically all its

subjects. Other schools joined in, including Columbia, Harvard,

Kansas State, Ohio State, NYU, Purdue, Tufts, and the

Universities of Akron, Arkansas, California, Florida, Hawaii,

Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Utah. Journalist

Bruce Bliven pondered: "Is radio to become a chief arm of

education? Will the classroom be abolished, and the child of the

future be stuffed with facts as he sits at home or even as he

walks about the streets with his portable receiving-set in his

pocket?"[8]

The students read textbooks and listened to broadcast lectures,

but attrition rates were very high, and there was no way to

collect tuition. By 1940 radio courses had virtually

disappeared.[8]

Talking motion pictures were the technology of choice in the

1930s and 1940s. They were used to train millions of draftees

during World War II in how to operate all sorts of equipment.

Any number of universities had televised classes starting in the

late 1940s at the University of Louisville.[9]

The Australian

School of the Air has used two-way shortwave radio starting

in 1951 to teach school children in remote locations. At many

universities in the 1980s special classrooms were linked to a

remote campus to provide closed-circuit video access to

specialized advanced courses for small numbers of students, and

many continue to operate. But this trend should not be

disconnected from the more general and historical process of

industrialization of education, in particular through teaching

machines, industry of textbook and educational networks[10]

There are striking anticipations of the MOOC of the 2010s in the

CBS TV series

Sunrise Semester, broadcast from the 1950s to the 1980s with

cooperation between CBS and NYU. Course credit was even offered

for participants in those early video courses[11]

In 1994,

James J. O'Donnell of the University of Pennsylvania taught

an Internet seminar, using gopher and email, on the life and

works of St. Augustine of Hippo, attracting over 500

participants from around the world.[12]

By 1994 hundreds of colleges had distance education

undergraduate degree programs, and there were 150 leading to

advanced degrees.[13]

The short lecture format used by many MOOCs developed from "Khan

Academy’s free archive of snappy instructional videos."[14]

In April 2007, Irish-based

ALISON (Advance Learning Interactive Systems Online)

launched its massively free online courses for basic education

and workplace skills training supported by advertising."[15]

Early MOOCs

MOOCs originated about 2008 within the

open educational resources (or OER) movement. Many of the

original courses were based on

connectivist theory, emphasizing that learning and knowledge

emerge from a network of connections. The term MOOC was coined

in 2008 during a course called "Connectivism

and Connective Knowledge" that was presented to 25

tuition-paying students in Extended Education at the

University of Manitoba in addition to 2,300 other students

from the general public who took the online class free of

charge. All course content was available through

RSS

feeds, and learners could participate with their choice of

tools: threaded discussions in Moodle, blog posts, Second Life,

and synchronous online meetings. The term was coined by Dave

Cormier of the

University of Prince Edward Island, and Senior

Research Fellow Bryan Alexander of the

National Institute for Technology in Liberal Education in

response to the course designed and led by

George Siemens of

Athabasca University and

Stephen Downes of the

National Research Council (Canada).[16]

Soon other independent MOOCs emerged. Jim Groom from The

University of Mary Washington and Michael Branson Smith of

York College, City University of New York, adopted this

course structure and hosted their own MOOCs through several

universities. Early MOOCs departed from formats that relied on

posted resources,

learning management systems, and structures that mix the

learning management system with more open web resources.[17]

MOOCs from private, non-profit institutions[18]

emphasized prominent faculty members and expanded open offerings

to existing subscribers (e.g., podcast listeners) into free and

open online courses.

Recent

developments

"The New York Times dubbed 2012 'The Year of the

MOOC,' and it has since become one of the hottest topics in

education. Time magazine said that free MOOCs open the

door to the 'Ivy League for the Masses.'”.[20]

This has been primarily due to the emergence of several

well-financed providers, associated with top universities,

including

Udacity,

Coursera, and

edX.[21]

In the fall of 2011 Stanford University launched three

courses, each of which had an enrollment of about 100,000.[22]

The first of those courses, Introduction Into AI, was launched

by

Sebastian Thrun and

Peter Norvig, with the enrollment quickly reaching

approximately 160,000 students. The announcement was followed

within weeks by the launch of two more MOOCs, by

Andrew Ng and

Jennifer Widom. Following the publicity and high enrollment

numbers of these courses,

Sebastian Thrun launched

Udacity and

Daphne Koller and

Andrew Ng launched

Coursera, both for-profit companies. Coursera subsequently

announced partnerships with several other universities,

including the

University of Pennsylvania,

Princeton University,

Stanford University, and

The University of Michigan.

Concerned about the commercialization of online education,

MIT launched the MITx not-for-profit later in the fall, an

effort to develop a free and open online platform. The inaugural

course, 6.002x, launched in March 2012.

Harvard joined the initiative, renamed

edX,

that spring, and

University of California, Berkeley joined in the summer. The

edX

initiative now also includes the

University of Texas System,

Wellesley College and the

Georgetown University.

In November 2012, the first high school MOOC was launched by

the

University of Miami Global Academy, UM's online high school.

The course became available for high school students preparing

for the SAT Subject Test in biology, providing access for

students from any high school. About the same time Wedubox,

first big MOOC in Spanish, started with the beta course

including 1,000 professors.[23]

On October 15, 2012 The University of New South Wales in

Australia launched UNSW Computing 1, the first MOOC by an

Australian University.[24]

The course was also the first MOOC to run on

OpenLearning, an online learning platform developed in

Australia, which provides features for group work, automated

marking, collaboration and

gamification. In late 2012, the UK's

Open university launched a British MOOC provider,

Futurelearn, as a separate company[25]

including provision of MOOCs from non-university partners.[26]

In March 2013 in a similar move for a homegrown platform

Open2Study was set up in Australia.[27][28]

Both Futurelearn and Open2Study intend to build on the

experience of their founding institutions in distance and online

education.

MOOC providers have also emerged in other countries,

including Iversity in Germany. Some organisations have also run

their own MOOCs – including Google's Power Search MOOC. As of

February 2013 dozens of universities had affiliated with MOOCs,

including many international institutions.[29][30]

In January 2013,

Udacity launched the first MOOCs-for-credit, in

collaboration with San Jose State University. This was followed

in May 2013 by the announcement of the first-ever entirely

MOOC-based Master's Degree, a collaboration between Udacity,

AT&T and the

Georgia Institute of Technology, costing $7,000.[31]

In June 2013, the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill launched Skynet

University,[32]

which offers MOOCs on the sole topic of introductory astronomy.

Participants gain access to the university's global network of

robotic telescopes, including telescopes in the Chilean Andes

and Australia. Skynet University incorporates popular social

media platforms, including YouTube,[33]

Facebook,[34]

and Twitter.[35]

During its first 13 months of operation (ending March 2013),

Coursera offered about 325 courses, with 30% in the sciences,

28% in arts and humanities, 23% in information technology, 13%

in business, and 6% in mathematics.[36]

Udacity offered 26 courses. Udacity's CS101, with an enrollment

of over 300,000 students, is the largest MOOC to date.

Related educational practices and courses

There are few standard practices or definitions in the field

yet. A number of other organisations such as

ALISON,

Khan Academy,

Peer-to-Peer University (P2PU) and

Udemy

are viewed as being similar to MOOCs, but differ in that they

work outside the university system or mainly provide individual

lessons that students may take at their own pace, rather than

having a massive number of students all working on the same

course schedule.[37][38][39]

Note, however, that Udacity differs from Coursera and edX in

that it does not have a calendar-based schedule (asynchronous);

students may start a course at any time. While some MOOCs such

as Coursera present lectures online, typical to those of

traditional classrooms, others such as Udacity offer interactive

lessons with activities, quizzes and exercises interspersed

between short videos and talks.

MOOC hype

Dennis Yang, President of MOOC provider

Udemy has suggested that MOOCs are in the midst

of a

hype cycle, with expectations undergoing a wild

swing. [40]

Many universities scrambled to join in the "next big thing",

as did more established

online education service providers such as

Blackboard Inc, in what has been called a "stampede." Dozens

of universities in Canada, Mexico, Europe and Asia have

announced partnerships with the large American MOOC providers.[29][41]

Nevertheless, by early 2013, questions emerged about whether

MOOCs were undergoing a

hype cycle and whether academia was "MOOC'd out."[40][42]

Instructional design approaches

According to Sebastian Thrun's testimony before The

President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology

(PCAST) on November 26, 2012, MOOC "courses are 'designed to be

challenges,' not lectures, and the amount of data generated from

these assessments can be evaluated 'massively using machine

learning' at work behind the scenes. This approach, he said,

dispels 'the medieval set of myths' guiding teacher efficacy and

student outcomes, and replaces it with evidence-based, 'modern,

data-driven' educational methodologies that may be the

instruments responsible for a 'fundamental transformation of

education' itself".[20]

Because of the massive scale of learners, and the likelihood of

a high student-teacher ratio, MOOCs require instructional design

that facilitates large-scale feedback and interaction. There are

two basic approaches:

-

Crowd-sourced interaction and feedback by leveraging the

MOOC network, e.g. for peer-review, group collaboration

- Automated feedback through objective, online

assessments, e.g. quizzes and exams

Connectivist MOOCs rely on the former approach; broadcast

MOOCs such as those offered by

Coursera or

Udacity rely more on the latter.[45]

Because a MOOC provides a way of connecting distributed

instructors and learners across a common topic or field of

discourse,[46]

some instructional design approaches to MOOCs attempt to

maximize the opportunity of connected learners who may or may

not know each other already, through their network. This may

include emphasizing collaborative development of the MOOC

itself, or of learning paths for individual participants.

The evolution of MOOCs has also seen innovation in

instructional materials. An emerging trend in MOOCs is the use

of nontraditional textbooks such as

graphic novels to improve students' knowledge retention.[47]

Others view the possibility of the videos and other material

produced by the MOOC as becoming the modern form of the

textbook. "MOOC is the new textbook," according to David

Finegold of

Rutgers University.[48]

Instructional cost of MOOC delivery

In 2013, the

Chronicle of Higher Education surveyed 103 professors who

had taught MOOCs. "Typically a professor spent over 100 hours on

his MOOC before it even started, by recording online lecture

videos and doing other preparation," though some instructors'

pre-class preparation was "a few dozen hours." The professors

then spent 8–10 hours per week on the course, including

participation in discussion forums, where they posted once or

twice a week.[49]

The medians were: 33,000 students enrolled in a class; 2,600

receiving a passing grade; and 1 teaching assistant helping with

the class. 74% of the classes used automated grading, and 34%

used peer grading. 97% of the instructors used original videos

in the course, 75% used open educational resources, and 27% used

other resources. 9% of the classes required the purchase of a

physical textbook, and 5% required the purchase of an e-book.[49][50]

In May 2013 Coursera announced that it would be offering the

free use of e-textbooks for some courses in partnership with

Chegg,

an online textbook-rental company. Students would need to use

Chegg's e-reader which limits copying and printing and could

only use a textbook while enrolled in the class.[51]

Involvement of alumni

In 2013 Harvard offered a popular class, The Ancient Greek

Hero, which thousands of Harvard students had taken over the

last few decades. It appealed to alumni to volunteer as online

mentors and discussion group managers. About 10 former teaching

fellows have also volunteered. The task of the volunteers, which

requires 3–5 hours of unpaid work per week, is to focus online

class discussion on the course material. The instructor,

Gregory Nagy, 70 in 2013, is author of The Best of the

Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry, Revised

Edition. The course, offered through edX, had 27,000

students registered.[52]

Connectivist design principles

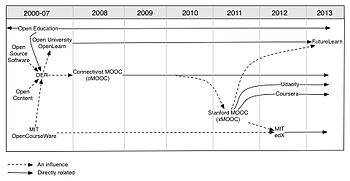

Development of MOOC providers [53]

As MOOCs have evolved, there appear to be two distinct types:

those that emphasize the connectivist philosophy, and those that

resemble more traditional and well-financed courses, such as

those offered by

Coursera and

edX.

To distinguish between the two,

Stephen Downes proposed the terms "cMOOC" and "xMOOC".[54]

Connectivist MOOCs are based on several principles stemming

from

connectivist pedagogy.[55][56][57][58]

The principles include:

- Aggregation. The whole point of a connectivist

MOOC is to provide a starting point for a massive amount of

content to be produced in different places online, which is

later aggregated as a newsletter or a web page accessible to

participants on a regular basis. This is in contrast to

traditional courses, where the content is prepared ahead of

time.

- The second principle is

remixing, that is, associating materials created within

the course with each other and with materials elsewhere.

- Re-purposing of aggregated and remixed materials

to suit the goals of each participant.

- Feeding forward, sharing of re-purposed ideas and

content with other participants and the rest of the world.

An earlier list (2005) of Connectivist principles[59]

from Siemens also informs the pedagogy behind MOOCs:

- Learning and knowledge rest in diversity of opinions.

- Learning is a process of connecting specialised nodes or

information sources.

- Learning may reside in non-human appliances.

- Capacity to know more is more critical than what is

currently known.

- Nurturing and maintaining connections is needed to

facilitate continual learning.

- Ability to see connections between fields, ideas, and

concepts is a core skill.

- Currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the intent

of all connectivist learning activities.

- Decision making is itself a learning process. Choosing

what to learn and the meaning of incoming information is

seen through the lens of a shifting reality. While there is

a right answer now, it may be wrong tomorrow due to

alterations in the information climate affecting the

decision.

It is suggested that connectivist MOOCs are in a better

position to support collaborative dialogue and knowledge

building than models adopting other approaches

[60][61]

Exams

and assessment

Three types of activities are usually conducted online in a

MOOC: direct presentation of information, such as a lecture or

video; interactive exploration of the material, such as

discussion boards, and assessment, such as exams and quizzes.

Assessment can be the most difficult activity to conduct online,

and the online version might appear to be quite different from

the bricks-and-mortar version.[62]

Special attention has been devoted to proctoring and the problem

of cheating.[63]

The two most common methods of MOOC assessment are

machine-graded multiple-choice quizzes or tests and

peer-reviewed written assignments.[62]

Machine grading of written assignments is also being developed.[64]

Peer review will often be based upon sample answers or

rubrics, which guide the grader on how many points to award

different answers. These rubrics cannot be as complex for peer

grading as they can be for grading by teaching assistants, but

students are expected to learn both by being the grader as well

as by having their work graded.[65]

Exams may be proctored at regional testing centers, though

this might limit the number of students who can take the course.

Other methods, including "eavesdropping technologies worthy of

the C.I.A." allow test taking at home or office, by using

webcams, or monitoring mouse clicks and typing styles.[63]

Special techniques such as

adaptive testing may be used, where the test tailors itself

given the student's previous answers, giving harder or easier

questions based upon the number of correct answers given.

MOOC

experiences

MOOCs typically do not offer academic credit or charge

tuition fees. Only about 10% of the tens of thousands of

students who may sign up complete the course.[1]

MOOCs attract large numbers of participants, sometimes several

thousands, most of whom participate peripherally ("lurk"). For

example, the first MOOC in 2008 had 2200 registered members, of

whom 150 were actively interacting at various times.[66]

Learners can control where, what, how, with whom they learn, but

different learners choose to exercise more or less of that

control. The goal is to re-define the very idea of a "course,"

creating an open network of learners with emergent and shared

content and interactions. A MOOC allows participants to form

connections through autonomous, diverse, open, and interactive

discourse.[67]

Most MOOCs that have featured "massive" participation have

been courses emphasizing learning on the web. "Students" are

often not traditional students in residence on a university

campus, but professionals who have already earned a degree,

educators, business people, researchers and others interested in

internet culture.[68]

Principles of

openness inform the creation, structure and operation of

MOOCs. The extent to which practices of Open Design in

educational technology[69]

are applied to a particular MOOC seem to vary with the planners

involved. Research by Kop and Fournier

[67] highlighted as major challenges for novice

learners on MOOCs the lack of social presence and the high level

of autonomy required to operate in such a learning environment.

According to some comments in MOOC discussion forums, features

that are normally associated with an educational activity can

appear to be completely missing. Structure, direction and

purpose sometimes seem lost in the scattering of discussions,

and this messiness, although it also creates a buzz, can make

following a line of discussion or creating meaning challenging.[citation

needed]

Table 1 Comparison of key aspects of MOOCs or Open

Education initiatives p8.jpgCompares some features

of current MOOC offerings eDX, Coursera, Udacity,

Udemy, P2P with respect to attributes:For profit;

free to access; certification fee; institutional

credit.Yuan, Li, and Stephen Powell. MOOCs and Open

Education: Implications for Higher Education White

Paper. University of Bolton: CETIS, 2013.

http://publications.cetis.ac.uk/2013/667.

One online MOOC reviewer,

Jonathan Haber, has tried to focus on questions of what

students are learning in MOOCs and who are the students

themselves. About half the students taking the courses are from

outside the United States, and many do not speak English as

their first language.[70]

He's found some of the courses to be very meaningful, even

though they are essentially about reading comprehension. Video

lectures followed by a few multiple choice questions can be

challenging since they are often the "right questions."

Discussion boards can seem paradoxical with the fewer

contributions leading to the best conversations. More discussion

comments can be "really, really thoughtful and really, really

misguided," with long discussions becoming mediocre rehashes or

"the same old stale left/right debate." Grading by peer review

has had mixed results. Three fellow students each grade one

written assignment for each assignment that they themselves

submit. The grading key or rubric tends to focus the grading,

but discourages more creative writing.[70]

A. J. Jacobs in an op-ed in the

New York Times graded his experience in 11 MOOC classes

overall as a "B".[71]

He rated his professors as '"B+", despite "a couple of

clunkers", even comparing them to pop stars and "A-list

celebrity professors." Nevertheless he rated teacher-to-student

interaction as a "D" since he had almost no contact with the

professors.

Convenience was the highest rated aspect of Jacob's course

experience, rated an "A", as he was able to watch lectures at

odd moments of the day. Student-to-student interaction and

assignments both received "B-" from Jacobs. Study groups that

didn't meet, trolls on message boards, and the relative slowness

of online vs. personal conversations lowered his rating on

student-to-student interaction. Assignments included multiple

choice quizzes and exams as well as essays and projects. He

found the multiple choice tests stressful and peer graded essays

painful, even though the peer reviewers tried to be kind. He

only completed 2 of the 11 classes he registered for.[71][72]

Students

served

Early plans and discussions often emphasized that MOOCs could

open up higher education to anybody in the world, especially to

underserved populations.[73]

As of 2013, the range of students registered appears to be

broad, diverse, and non-traditional, but is concentrated among

English-speakers in rich countries.

A course billed as "Asia's first MOOC" given by the

Hong Kong University of Science and Technology through

Coursera starting in April 2013 had 17,000 students registered.

About 60% were from "rich countries" with many of the rest from

middle-income countries in Asia, South Africa, or America, like

Brazil or Mexico. There were fewer students from areas with more

limited access to the internet, and students from the People's

Republic of China may have been discouraged by Chinese

government policies.[74]

“We have the whole gamut of older and younger, experienced

and less experienced students, and also academics and probably

some people who are experts in related fields,” according to

Naubahar Sharif who teaches the class on Science,

Technology and Society in China. “We do have students from

China as well, in places where Internet connections are more

reliable.”[74]

During its first 13 months in operation, ending March 2013,

Coursera registered about 2.8 million learners with[36]

- 27.7% from the United States

- 8.8% from India

- 5.1% from Brazil

- 4.4% from the United Kingdom

- 4.0% from Spain

- 3.6% from Canada

- 2.3% from Australia

- 2.2% from Russia

- 41.9% from the rest of the world

Daphne Koller, a co-founder of Coursera, stated in May 2013

that a majority of the people taking Coursera courses had

already earned college degrees.[75]

According to a Stanford University study of a more general

group of students "active learners" – anybody who participated

beyond just registering – showed a very unbalanced gender

proportion. Sixty-four percent of high school active learners

were male, with 88% male for both undergraduate- and

graduate-level courses.[76]

Completion

rates

Completion rates are typically very low, with a steep

drop-off in student participation starting in the first week. In

the course Bioelectricity, Fall 2012 at Duke University,

12,725 students enrolled, but only 7,761 ever watched a video,

3,658 attempted a quiz, 345 attempted the final exam, and 313

passed, earning a certificate.[77][78]

Broad-based but early data from Coursera suggest a completion

rate of 7%–9%.[68]

Most registered students don't intend to complete the course,

according to Coursera founders Daphne Koller and Andrew Ng, but

rather to explore the general topic. The completion rate for

students who complete the first assignment is about 45 percent.

Students paying $50 for a feature designed to prevent cheating

on exams have completion rates of about 70 percent.[79]

One online survey listed a "top ten" list of reasons for not

completing a course.[80]

These most common reasons were that the course required too much

time, was too difficult, or conversely, too basic. Reasons

related to poor course design included "lecture fatigue" related

to a perceived tendency to simply recreate the bricks-and-mortar

course, lack of a proper introduction to course technology and

format, and clunky technology and trolling on discussion boards.

Hidden costs were cited including by those who found that

required readings were from expensive texts written by the

instructor. Other non-completers were "just shopping around"

when they registered, or were participating simply for the

knowledge rather than a credential.

A study from Stanford University's Learning Analytics group

identifies four type of MOOC students: auditors, who watched

video throughout the course, but took few quizzes or exams;

completers, who viewed most lectures and took part in most

assessments; disengaging learners, who took part only at the

start of the course; and sampling learners, who might only watch

the lectures at various times during the course.[76]

Based on data from high school, undergraduate, and graduate

MOOCs. They identified the following percentages in each group:[81]

| Course |

Auditing |

Completing |

Disengaging |

Sampling |

| High school |

6% |

27% |

28% |

39% |

| Undergraduate |

6% |

8% |

12% |

74% |

| Graduate |

9% |

5% |

6% |

80% |

Economics, business models and industry structure

MOOCs are widely seen as a major part of a larger

disruptive innovation taking place in the higher education

industry.[82][83][84]

In particular, the many services at present offered under the

current university business model are likely to become

unbundled and sold to the universities' diverse customers

individually or in newly formed bundles.[85][86]

These services include research, curriculum design, content

generation (such as textbooks), teaching, assessment and

certification (such as granting degrees), and student placement.

MOOCs threaten the current business model by potentially selling

teaching, assessment, and/or placement separately from the

current package of services.[82][87][88]

James Mazoue, Director of Online Programs at

Wayne State University describes one possible innovation:

The next disruptor will likely mark a tipping point: an

entirely free online curriculum leading to a degree from

an accredited institution. With this new business model,

students might still have to pay to certify their

credentials, but not for the process leading to their

acquisition. If free access to a degree-granting

curriculum were to occur, the business model of higher

education would dramatically and irreversibly change. [89]

But how universities will benefit by "giving our product away

free online" is not yet clear.[90]

No one's got the model that's going to work yet. I

expect all the current ventures to fail, because the

expectations are too high. People think something will

catch on like wildfire. But more likely, it's maybe a

decade later that somebody figures out how to do it and

make money.

—James Grimmelmann, New York Law School professor [90]

Business model

The

freemium business model, drawn from

Silicon Valley companies like

Google is a leading candidate. In this model the basic

product – the course content – is given away free. “Charging for

content would be a tragedy,” said Andrew Ng. But premium

services such as certification or placement would be charged a

fee.[36]

Coursera has begun charging licensing fees for educational

institutions that use Coursera materials. The very popular

introductory or "gateway" courses and some remedial courses may

earn them the most fees. Universities will benefit by attracting

new students to follow-on fee-charging classes or they may offer

blended courses, supplementing MOOC material with face-to-face

instruction. Both Coursera and Udacity have begun to charge

employers for hiring access to the best students. Students may

be able to pay to take a proctored exam which could lead to them

getting transfer credit at a degree-granting university, or

Coursera may charge $20 to $50 for certificates of completion.[90]

The table below illustrates some of the revenue sources

currently being discussed by three MOOC providers.

| edX |

Coursera |

UDACITY |

|

|

- Certification

- Secure assessments

- Employee recruitment

- Applicant screening

- Human tutoring or assignment marking

- Enterprises pay to run their own training

courses

- Sponsorships

- Tuition fees

|

- Certification

- Employers paying to recruit talented students

- Students résumés and job match services

- Sponsored high-tech skills courses

|

Overview of potential revenue sources for three MOOC

providers[91]

In February 2013 the

American Council on Education announced that they would

recommend that its members accept transfer credit from a few

MOOC courses, though even the universities who deliver the

courses said that they would not accept the transfer credit. The

high tuition fees charged by these elite universities give them

a major incentive against accepting transfer credit from free

classes.[92]

Academic Partnerships, a company that helps public

universities move their courses online, also hopes for follow-on

revenue. According to its chairman, Randy Best “We started it,

frankly, as a campaign to grow enrollment. But 72 to 84 percent

of those who did the first course came back and paid to take the

second course.”[93]

While Coursera takes a large cut of any revenue generated –

but requires no minimum payment – the not-for-profit EdX has a

minimum required payment from course providers, but then takes a

smaller cut of any profit made, tied to the amount of support

required for each course[94]

Industry

structure

The industry that has rapidly grown to provide MOOCs has an

unusual structure consisting of linked groups including the

actual for-profit or non-profit MOOC providers, the larger

non-profit sector, universities, related companies, and

venture capitalists.

The Chronicle of Higher Education lists the major

providers as the non-profits the

Khan Academy, and

edX,

and the for-profits

Udacity and

Coursera.[95]

The larger non-profit organizations with commitments to the

field include the

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the

MacArthur Foundation, the

National Science Foundation, and the

American Council on Education. Major universities involved

include

Stanford,

Harvard,

MIT, the

University of Pennsylvania,

CalTech, the

University of Texas at Austin, the

University of California at Berkeley, and

San Jose State University.[95]

Related companies include

Google and the publisher

Pearson PLC. Venture capitalists include

Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers,

New Enterprise Associates and

Andreessen Horowitz.[95]

The success of MOOCs is expected to change the structure of

the higher education industry. As the philosophy faculty at San

Jose State University wrote in an open letter to Harvard

University professor and MOOC teacher

Michael Sandel:

Should one-size-fits-all vendor-designed blended courses

become the norm, we fear two classes of universities

will be created: one, well-funded colleges and

universities in which privileged students get their own

real professor; the other, financially stressed private

and public universities in which students watch a bunch

of video-taped lectures. [96]

Technology

Producing and delivering MOOCs is a technological challenge.

Unlike traditional courses, MOOCs require videographers,

instructional designers, IT specialists, and platform

specialists. An instructor at

Georgia Tech reports that they have a team of 19 people

working on MOOCs, and that more are needed.[97]

The platforms are designed to be available to students at all

times during the course, unlike traditional courses and often

have the same technological requirements as media/content

sharing websites due to the large number of students involved

with a class. As a result, MOOCs use

Cloud computing and other modern technology involved with

Application software.

Course delivery involves non-synchronous access to videos and

other learning material, exams and other assessment, as well as

online forums. Engagement is also a core concept behind course

delivery. Before 2013 each MOOC tended to develop its own

delivery platform. EdX has planned to make its delivery software

freely available as an open-source package and in April 2013

joined with Stanford University, which previously had its own

platform called Class2Go, to work on a joint open-source

platform. The platform, called XBlock SDK, is available to the

public under the

Affero GPL open source license, which requires that all

improvements to the platform be publicly posted and made

available under the same license.[98]

John Mitchell, a Stanford Vice Provost, said that the goal was

to provide the “Linux of online learning.”.[99]

This is unlike other platforms like Coursera that have developed

their own software for their specific site.[100]

Potential

benefits

The MOOC Guide[101]

lists 12 benefits of a MOOC:

- You can organize a MOOC in any setting that has

connectivity (which can include the Web, but also local

connections via Wi-Fi e.g.)

- You can organize it in any language you like (taking

into account the main language of your target audience)

- You can use any online tools that are relevant to your

target region or that are already being used by the

participants

- You can move beyond time zones and physical boundaries

- It can be organized as quickly as you can inform the

participants (which makes it a powerful format for priority

learning in e.g. aid relief)

- Contextualized content can be shared by all

- Learning happens in a more informal setting

- Learning can also happen incidentally thanks to the

unknown knowledge that pops up as the course participants

start to exchange notes on the course’s study

- You can connect across disciplines and

corporate/institutional walls

- You don’t need a degree to follow the course, only the

willingness to learn (at high speed)

- You add to your own personal learning environment and/or

network by participating in a MOOC

- You will improve your lifelong learning skills, for

participating in a MOOC forces you to think about your own

learning and knowledge absorption

Challenges and criticisms

The MOOC Guide[101]

lists 5 possible challenges for collaborative-style MOOCs:

- It feels chaotic as participants create their own

content

- It demands

digital literacy

- It demands time and effort from the participants

- It is organic, which means the course will take on its

own trajectory (you have got to let go).

- As a participant you need to be able to self-regulate

your learning and possibly give yourself a learning goal to

achieve.

In addition, other concerns have been raised regarding the

nature of MOOCs, including:

- Concerns have been raised around the 'territorial'

nature of MOOCs[102]

with little discussion around: 1) who enrolls in/completes

courses; 2) The implications of courses scaling across

country borders, and potential difficulties with relevance

and knowledge transfer; 3) the need for territory-specific

study of locally relevant issues and needs.

- Other features associated with early MOOCs, such as open

licensing of content, open structure and learning goals,

community-centeredness, etc. may not be present in all MOOC

projects.[2]

The effect of MOOCs on the structure of higher education has

been severely questioned, for example by

Moshe Y. Vardi in an article entitled "Will MOOCs destroy

academia?" He describes the problem as being an "absence of

serious pedagogy in MOOCs", indeed in all of higher education,

with a rather uninspiring MOOC format of "short, unsophisticated

video chunks, interleaved with online quizzes, and accompanied

by social networking." An underlying reason is simple cost

cutting pressures, which are likely to hamstring the higher

education industry if followed without proper analysis.[103]

By majority vote (60%),

Amherst College faculty rejected the opportunity to work

with edX based on a perceived incompatibility of their small

liberal arts college seminar-style classes and personalized

feedback with the demands of a MOOC. Some were concerned about

issues such as the "information dispensing" teaching model of

lectures followed by exams, the use of multiple-choice exams,

and peer-grading. However, others were interested in exploring

alternatives to that model. The effect of MOOCs on the structure

of higher education was also a concern, especially the potential

of taking funds away from second- and third-tier institutions

and centralizing higher education, and of perpetuating a faculty

"star system".[64]

See also

References

-

^

a

b

Lewin, Tamar (February 20,

2013).

"Universities Abroad Join Partnerships on the Web".

New York Times.

Retrieved March 6, 2013.

-

^

a

b

Wiley, David. "The

MOOC Misnomer". July 2012

-

^

Cheverie, Joan.

"MOOCs an Intellectual Property: Ownership and Use

Rights".

Retrieved April 18, 2013.

-

^ Videos by

Dave Cormier with a grant from the

University of Prince Edward Island,

What is...,

Success...,

Knowledge..., accessed March 6, 2013

-

^ Saettler,

Paul (1968), A History of Instructional Technology, New

York…, Mc Graw Hill.

-

^ J.J.

Clark, "The Correspondence School—Its Relation to

Technical Education and Some of Its Results," Science

(1906) 24#611 pp. 327–334

in JSTOR

-

^ Joseph F.

Kett, Pursuit of Knowledge Under Difficulties: From

Self-Improvement to Adult Education in America

(1996) pp 236–8

-

^

a

b

Matt, Susan; Fernandez, Luke (April 23, 2013).

"Before MOOCs, 'Colleges of the Air'". Chronicle of

Higher Education.

-

^ Dwayne D.

Cox and William J. Morison, The University of

Louisville (1999) pp 115–17

-

^ P.

Moeglin, Les industries éducatives, Paris, Presses

universitaires de France, 2010

-

^ Professor

Floyd Zulli of NYU was an animating spirit in this

enterprise:

"CBS Sunrise Semester".

-

^ For

description, see:

"Augustine on the Infobahn".;

for O'Donnell's reflections on the current context, see

"The Future Is Now, and Always Has Been".

-

^ James P.

Duffy, How to Earn a College Degree Without Going to

College (2nd ed. 1994) p.5

-

^

Pappano, Laura.

"The Year of the Mooc". The New York Times

(The New York Times).

Retrieved November 29, 2012.

-

^

Booker, Ellis.

"Early MOOC Takes a Different Path".

-

^

Attention les MOOC!?! Mois de la pédagogie universitaire

in English with introduction in French, Dave Cormier,

April 18, 2013

-

^

Masters, Ken (2011).

"A brief guide to understanding MOOCs". The

Internet Journal of Medical Education 1 (Num.

2).

-

^ The

College of St. Scholastica, "Massive

Open Online Courses", (2012)

-

^

TED talks:

Shimon Schocken,

Daphne Koller,

Peter Norvig,

Salman Khan, accessed March 6, 2013.

-

^

a

b

"Librarians and the Era of the MOOC".

Nature.com. May 9, 2013.

Retrieved May 11, 2013.

-

^ Smith,

Lindsey "5

education providers offering MOOCs now or in the future".

July 31, 2012.

-

^

Richard Pérez-Peña (July 17,

2012).

"Top universities test the online appeal of free".

The New York Times.

Retrieved July 18, 2012.

-

^

Horacio Reyes.

"History of a revolution in e-learning". Revista

Educacion Virtual.

Retrieved August 10, 2012.

-

^

"Brave new free online course for UNSW". Afr.com.

Retrieved June 3, 2013.

-

^

Claire Shaw (2012-12-20).

"FutureLearn is UK's chance to 'fight back', says OU

vice-chancellor | Higher Education Network | Guardian

Professional". Guardian.

Retrieved 2013-05-30.

-

^

Tuesday, February 19th, 2013

(2013-02-19).

"U.K. MOOCs Alliance, Futurelearn, Adds Five More

Universities And The British Library — Now Backed By 18

Partners". TechCrunch.

Retrieved 2013-05-30.

-

^

"PR Newswire UK: Australia sets the scene for free

online education - MELBOURNE, Australia, March 20, 2013

/PRNewswire/". australia: Prnewswire.co.uk.

Retrieved 2013-05-30.

-

^

"The Aussie Coursera? A new homegrown MOOC platform

arrives". Theconversation.com.

Retrieved 2013-05-30.

-

^

a

b

Tamar Lewin (February 20,

2013).

"Universities Abroad Join Partnerships on the Web".

The New York Times.

Retrieved February 21, 2013.

-

^

Steve Kolowich (February 21,

2013).

"Competing MOOC Providers Expand into New Territory—and

Each Other's" (blog by expert journalist). The

Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved February 21, 2013.

-

^

"Georgia Tech, Udacity Shock Higher Ed With $7,000

Degree". Forbes. 2012-04-18.

Retrieved 2013-05-30.

-

^

"Skynet University".

-

^

"Skynet University on YouTube".

-

^

"Skynet on Facebook".

-

^

"Skynet on Twitter".

-

^

a

b

c

Waldrop, M. Mitchell;

Nature magazine (March 13, 013).

"Massive Open Online Courses, aka MOOCs, Transform

Higher Education and Science". Scientific

American.

Retrieved April 28, 2013.

-

^ Yuan, Li,

and Stephen Powell.

MOOCs and Open Education: Implications for Higher

Education White Paper. University of Bolton: CETIS,

2013. pp. 7–8.

-

^

"What You Need to Know About MOOCs".

Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved March 14, 2013.

-

^

"Open Education for a global economy".

-

^

a

b

Yang, Dennis (March 14, 2013).

"Are We MOOC'd Out?". Huffington Post.

Retrieved April 5, 2013.

-

^ Laura

Pappano.

The Year of the MOOC – The New York Times. November

2, 2012

-

^

Skapinker, Michael (March

20, 2013).

"Open web courses are massively overhyped".

Financial Times.

Retrieved April 5, 2013.

-

^

"10 Steps to Developing an Online Course: Walter

Sinnott-Armstrong".

Duke University.

Retrieved March 20, 2013.

-

^

"Designing, developing and running (Massive) Online

Courses by George Siemens".

Athabasca University. September 12, 2012.

Retrieved March 26, 2013.

-

^ Carson,

Steve. "What

we talk about when we talk about automated assessment"

July 23, 2012

-

^

"George Siemens on Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs)".

YouTube. Retrieved

2012-09-18.

-

^

Price, Matthew (March 1,

2013).

"First massive open online course at University of

Oklahoma to feature graphic novel". The Oklahoman.

Retrieved 2013-03-01.

-

^

Young, Jeffrey R. (January

27, 2013).

"The Object Formerly Known as the Textbook".

Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved March 14, 2013.

-

^

a

b

Kolowich, Steven (March 26,

2013).

"The Professors Who Make the MOOCs".

Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved March 26, 2013.

-

^

"Additional Results From The Chronicle's Survey".

Chronicle of Higher Education. March 26, 2013.

Retrieved March 26, 2013.

-

^

New, Jake (May 8, 2013).

"Partnership Gives Students Access to a High-Price Text

on a MOOC Budget". Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved May 14, 2013.

-

^

Richard Perez-Pena (March

25, 2013).

"Harvard Asks Graduates to Donate Time to Free Online

Humanities Class By RICHARD PÉREZ-PEÑA Published:".

The New York Times.

Retrieved March 26, 2013.

-

^

Yuan, Li, and Stephen Powell. MOOCs and Open Education:

Implications for Higher Education White Paper.

University of Bolton: CETIS, 2013. p.6

-

^

Siemens, George.

"MOOCs are really a platform". Elearnspace.

Retrieved 2012-12-09.

-

^ Downes,

Stephen

"'Connectivism' and Connective Knowledge", Huffpost

Education, January 5, 2011, accessed July 27, 2011

-

^ Kop, Rita

"The challenges to connectivist learning on open online

networks: Learning experiences during a massive open

online course", International Review of Research in

Open and Distance Learning, Volume 12, Number 3, 2011,

accessed November 22, 2011

-

^ Bell,

Frances

"Connectivism: Its Place in Theory-Informed Research and

Innovation in Technology-Enabled Learning",

International Review of Research in Open and Distance

Learning, Volume 12, Number 3, 2011, accessed July 31,

2011

-

^ Downes,

Stephen.

"Learning networks and connective knowledge",

Instructional Technology Forum, 2006, accessed July 31,

2011

-

^

"Dialogue and connectivism: A new approach to

understanding and promoting dialogue-rich networked

learning | Ravenscroft | The International Review of

Research in Open and Distance Learning". Irrodl.org.

Retrieved 2012-09-18.

-

^ Dialogue

and Connectivism: A New Approach to Understanding and

Promoting Dialogue-Rich Networked Learning

[1] Andrew Ravenscroft International Review of

Research in Open and Distance Learning Vol. 12.3 March –

2011, Learning Technology Research Institute (LTRI),

London Metropolitan University, UK

-

^ S.F. John

Mak, R. Williams, and J. Mackness,

Blogs and Forums as Communication and Learning Tools in

a MOOC, Proceedings of the 7th International

Conference on Networked Learning (2010)

-

^

a

b

Degree of Freedom – an adventure in online learning,

MOOC Components – Assessment, March 22, 2013.

-

^

a

b

Eisenberg, Anne (March 2,

2013).

"Keeping an Eye on Online Test-Takers". New York

Times. Retrieved

April 19, 2013.

-

^

a

b

Rivard, Ry (April 19, 2013).

"EdX Rejected". Inside Higher Education.

Retrieved April 22, 2013.

-

^

Wong, Michael (March 28,

2013).

"Online Peer Assessment in MOOCs: Students Learning from

Students". Centre for Teaching, Learning and

Technology Newsletter. University of British

Columbia. Retrieved

April 20, 2013.

-

^ Mackness,

Jenny, Mak, Sui Fai John, and Williams, Roy

"The Ideals and Reality of Participating in a MOOC",

Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on

Networked Learning 2010

-

^

a

b

Kop, Rita, and Fournier,

Helene

"New Dimensions to Self-Directed Learning in an Open

Networked Learning Environment", International

Journal of Self-Directed Learning, Volume 7, Number 2,

Fall 2010

-

^

a

b

"MOOCs on the Move: How Coursera Is Disrupting the

Traditional Classroom" (text and video).

Knowledge @ Wharton. University of Pennsylvania.

November 7, 2012.

Retrieved April 23, 2013.

-

^

[2][dead

link]

-

^

a

b

Bombardieri, Marcella (April

14, 2013).

"Can you MOOC your way through college in one year?".

Boston Globe.

Retrieved April 23, 2013.

-

^

a

b

Jacobs, A.J. (April 21,

2013).

"Two Cheers for Web U!". New York Times, Sunday

Review. Retrieved

April 23, 2013.

-

^

"Making the most of MOOCs: the ins and outs of

e-learning" (Radio interview and call-in). Talk

of the Nation. National Public Radio. April 23, 2013.

Retrieved April 23, 2013.

-

^ See, e.g.

the first 3 minutes of the video

"Daphne Koller: What we're learning from online

education". TED (conference)|TED Talks. June 2012.

Retrieved April 23, 2013.

-

^

a

b

Sharma, Yojana (April 22, 2013).

"Hong Kong MOOC Draws Students from Around the World".

Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved April 23, 2013.

reprinted from University World News

-

^ Steve

Kolowich,

"In Deals With 10 Public Universities, Coursera Bids for

Role in Credit Courses," Chronicle of Higher

Education May 30, 2013

-

^

a

b

MacKay, R.F. (April 11, 2013).

"Learning analytics at Stanford takes huge leap forward

with MOOCs". Stanford Report. Stanford

University. Retrieved

April 22, 2013.

-

^

Catropa, Dayna (February 24,

2013).

"Big (MOOC) Data". Inside Higher Ed.

Retrieved March 27, 2013.

-

^

Jordan, Katy.

"MOOC Completion Rates: The Data".

Retrieved April 23, 2013.

-

^

Kolowich, Steve (April 8,

2013).

"Coursera Takes a Nuanced View of MOOC Dropout Rates".

The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved April 19, 2013.

-

^

"MOOC Interrupted: Top 10 Reasons Our Readers Didn’t

Finish a Massive Open Online Course". Open

Culture.

Retrieved April 21, 2013.

-

^

René F. Kizilcec; Chris

Piech, Emily Schneider.

"Deconstructing Disengagement: Analyzing Learner

Subpopulations in Massive Open Online Courses".

LAK conference presentation.

Retrieved April 22, 2013.

-

^

a

b

Barber, Michael; Katelyn Donnelly, Saad Rizvi.

Forward by

Lawrence Summers (March 2013).

An Avalanche is Coming; Higher Education and the

Revolution Ahead. London:

Institute for Public Policy Research. p. 71.

Retrieved March 14, 2013.

-

^

Parr, Chris (March 14,

2013).

"Fund ‘pick-and-mix’ MOOC generation, ex-wonk advises".

Times Higher Education (London).

Retrieved March 14, 2013.

-

^

Watters, Audrey (September 5,

2012).

"Unbundling and Unmooring: Technology and the Higher Ed

Tsunami". Educause Review.

Retrieved March 14, 2013.

-

^

Carey, Kevin (September 3,

2012).

"Into the Future With MOOC's".

Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved March 20, 2013.

-

^

Harden, Nathan (January

2013).

"The End of the University as We Know It". The

American Interest.

Retrieved March 26, 2013.

-

^

Zhu, Alex (September 6,

2012).

"Massive Open Online Courses – A Threat Or Opportunity

To Universities?". Forbes.

Retrieved March 14, 2013.

-

^

Shirky, Clay (December 17,

2012).

"Higher education: our MP3 is the mooc".

The Guardian.

Retrieved March 14, 2013.

-

^

Mazoue, James G. (January 28,

2013).

"The MOOC Model: Challenging Traditional Education".

EDUCAUSE Review Online.

Retrieved March 26, 2013.

-

^

a

b

c

Lewin, Tamar (January 6,

2013).

"Students Rush to Web Classes, but Profits May Be Much

Later".

New York Times.

Retrieved March 6, 2013.

-

^ Yuan, Li,

and Stephen Powell. MOOCs and Open Education:

Implications for Higher Education White Paper.

University of Bolton: CETIS, 2013.

http://publications.cetis.ac.uk/2013/667, p.10

-

^

Korn, Melissa (February 7,

2013).

"Big MOOC Coursera Moves Closer to Academic Acceptance".

Wall Street Journal.

Retrieved March 8, 2013.

-

^ Tamar

Lewin.

Public Universities to Offer Free Online Classes for

Credit. January 23, 2013

-

^

Kolowich, Steve (2013-02-21).

"How EdX Plans to Earn, and Share, Revenue From Free

Online Courses - Technology - The Chronicle of Higher

Education". Chronicle.com.

Retrieved 2013-05-30.

-

^

a

b

c

"Major Players in the MOOC Universe". Chronicle

of Higher Education. April 29, 2013.

Retrieved April 29, 2013.

-

^

"San Jose State to Michael Sandel: Keep your MOOC off

our campus".

Boston Globe. May 3, 2013.

Retrieved May 7, 2013.

-

^

Head, Karen (April 3, 2013).

"Sweating the Details of a MOOC in Progress".

Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved April 6, 2013.

-

^

"edX Takes First Step toward Open Source Vision by

Releasing XBlock SDK". www.edx.org. edX.

Retrieved April 6, 2013.

-

^

Young, Jeffrey R. (April 5,

2013).

"Stanford U. and edX Will Jointly Build Open-Source

Software to Deliver MOOCs".

Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved April 3, 2013.

-

^

"What is Coursera's Stack?". www.quora.org.

Qoura. Retrieved

April 8, 2013.

-

^

a

b

"Benefits and Challenges of a MOOC". MoocGuide. Jul

7, 2011<!- – 11:27 pm -->.

Retrieved February 4, 2013.

-

^

Olds, Kris (December 3,

2012).

"On the territorial dimensions of MOOCs". Inside

Higher Ed. Retrieved

February 4, 2013.

-

^

Vardi, Moshe Y. (November

2012).

"Will MOOCs destroy academia?". Communications of

the ACM 55 (11): 5.

Retrieved April 23, 2013.

External links and further reading

-

"MOOC pedagogy: the challenges of developing for Coursera"

-

"Babson Survey Research Group: National reports on growth of

online learning in US Higher Education"

- A. McAuley, B. Stewart, G, Siemens and D. Cormier,

The MOOC Model for Digital Practice (2010)

- Daniel, John (2012) Making sense of MOOCs: musings in a

maze of myth, paradox and possibility, Research paper

presented as a fellow of the Korea National Open University,

retrieved 13 October 2012 from

http://sirjohn.ca/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/120925MOOCspaper2.pdf

- D. Levy,

Lessons Learned from Participating in a Connectivist Massive

Online Open Course (MOOC), (2011)

- UNLOCKING the GATES: How and Why Leading Universities

Are Opening Up Access To Their Courses; Taylor Walsh,

Princeton University Press, 2011.

ISBN 978-0-691-14874-8

- Stephen Carson and Jan Philipp Schmidt.

The Massive Open Online Professor. Academic Matters: The

Journal of Higher Education, May 2012.

-

BBC interviews Jimmy Wales on MOOCs, May 1, 2013

- Shannon Bohle.

Librarians and the Era of the MOOC. Nature.com, May 9,

2013.

-

A Comprehensive List of MOOC Providers

|

|

|

1)

scrivi

le parole inglesi dentro la

striscia gialla

2)

seleziona il testo

3)

clicca "Ascolta il testo"

DA INGLESE A ITALIANO

Inserire

nella casella Traduci la parola

INGLESE e cliccare

Go.

DA ITALIANO A INGLESE

Impostare INGLESE anziché italiano e

ripetere la procedura descritta.

|

|