-

July

-

Margherita Hack

-

Idiom

-

Laurel and Hardy

-

Cloud computing

-

Fast food

-

Coursera

-

Tour de France

-

English modal verbs

-

Hartz concept

-

American Civil War

-

Florence

-

Rita Levi Montalcini

-

Flier (pamphlet)

-

Credit rating agency

-

Crusades

-

Web browser

-

David Bowie

-

English people

-

Cyberwarfare

-

Password

-

iOS 7

-

Massive open online course

-

Arthur Conan Doyle

-

Defense of Marriage Act

-

List of Italian musical terms used in English

-

Number

-

Unique selling proposition (USP)

-

Transatlantic Free Trade Area

-

Robin Hood

-

Louvre

|

WIKIMAG n. 8 - Luglio 2013

Arthur Conan Doyle

Text is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional

terms may apply. See

Terms of

Use for details.

Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the

Wikimedia Foundation,

Inc., a non-profit organization.

Traduzione

interattiva on/off

- Togli il segno di spunta per disattivarla

|

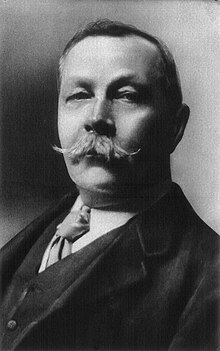

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

| Born |

Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle

22 May 1859

Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died |

7 July 1930 (aged 71)

Crowborough, East Sussex, England |

| Occupation |

Novelist, short story writer, poet,

physician |

| Nationality |

Scottish |

| Citizenship |

British |

| Genres |

Detective fiction, fantasy, science

fiction,

historical novels, non-fiction |

| Notable work(s) |

Stories of Sherlock Holmes

The Lost World |

|

| Signature |

|

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle

DL (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930[1])

was a Scottish physician and writer who is most noted for his

fictional stories about the detective

Sherlock Holmes, which are generally considered milestones

in the field of

crime fiction. He is also known for writing the fictional

adventures of a second character he invented,

Professor Challenger. He was a prolific writer whose other

works include fantasy and science fiction stories, plays,

romances, poetry, non-fiction, and historical novels.

Life and

career

Early life

Arthur Conan Doyle was born on 22 May 1859 at 11 Picardy

Place,

Edinburgh, Scotland.[2][3]

His father,

Charles Altamont Doyle, was born in England but of Irish

descent, and his mother, born Mary Foley, was Irish. They

married in 1855.[4]

In 1864 the family dispersed due to Charles's growing alcoholism

and the children were temporarily housed across Edinburgh. In

1867, the family came together again and lived in squalid

tenement flats at 3 Sciennes Place.[5]

Supported by wealthy uncles, Conan Doyle was sent to the

Roman Catholic

Jesuit

preparatory school

Hodder Place,

Stonyhurst, at the age of nine (1868-1870). He then went on

to

Stonyhurst College until 1875. From 1875 to 1876, he was

educated at the Jesuit school

Stella Matutina in

Feldkirch, Austria.[5]

Despite attending a Jesuit school, he would later reject the

Catholic religion and become an agnostic.[6]

From 1876 to 1881 he studied medicine at the

University of Edinburgh, including a period working in the

town of

Aston

(now a district of

Birmingham) and in Sheffield, as well as in Shropshire at

Ruyton-XI-Towns.[7]

While studying, Conan Doyle began writing short stories. His

earliest extant fiction, "The Haunted Grange of Goresthorpe",

was unsuccessfully submitted to

Blackwood's Magazine.[5]

His first published piece "The Mystery of Sasassa Valley", a

story set in South Africa, was printed in

Chambers's Edinburgh Journal on 6 September 1879.[5][8]

On 20 September 1879, he published his first non-fiction

article, "Gelsemium

as a Poison" in the

British Medical Journal.[5]

Following his studies at university, Conan Doyle was employed

as a doctor on the Greenland whaler Hope of Peterhead, in

1880,[9]

and, after his graduation, as a ship's surgeon on the SS

Mayumba during a voyage to the West African coast, in 1881.[5]

He completed his doctorate on the subject of

tabes dorsalis in 1885.[10]

Doyle's father died in 1893, in the

Crichton Royal,

Dumfries, after many years of psychiatric illness.[11][12]

Name

Although Doyle is often referred to as "Conan Doyle", whether

this should be considered a compound surname is uncertain. The

entry in which his baptism is recorded in the register of

St Mary's Cathedral,

Edinburgh, gives "Arthur Ignatius Conan" as his Christian

names, and simply "Doyle" as his surname. It also names Michael

Conan as his

godfather.[13]

The cataloguers of the

British Library and the

Library of Congress treat "Doyle" alone as his surname.[14]

Steven Doyle, editor of the Baker Street Journal, has

written

Conan was Arthur's middle name. Shortly after he

graduated from high school he began using Conan as a

sort of surname. But technically his last name is simply

"Doyle". [15]

When knighted he was gazetted as Doyle, not under the

compound Conan Doyle.[16]

Nevertheless, the actual use of a compound surname is

demonstrated by the fact that Doyle's second wife was known as

"Jean Conan Doyle" rather than "Jean Doyle".[17]

Writing career

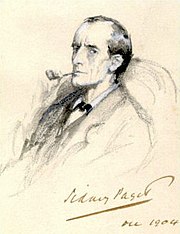

Portrait of Sherlock Holmes by Sidney Paget, 1904

In 1882 he joined former classmate George Turnavine Budd as

his partner at a medical practice in

Plymouth, but their relationship proved difficult, and Conan

Doyle soon left to set up an independent practice.[5][18]

Arriving in

Portsmouth in June of that year with less than £10 (£700

today[19])

to his name, he set up a medical practice at 1 Bush Villas in

Elm Grove,

Southsea.[20]

The practice was initially not very successful. While waiting

for patients, Conan Doyle again began writing stories and

composed his first novels, The Mystery of Cloomber, not

published until 1888, and the unfinished Narrative of John

Smith, which would go unpublished until 2011.[21]

He amassed a portfolio of short stories including "The Captain

of the Pole-Star" and "J. Habakuk Jephson's Statement", both

inspired by Doyle's time at sea.[5]

Doyle struggled to find a publisher for his work. His first

significant piece,

A Study in Scarlet, was taken by

Ward Lock & Co on 20 November 1886, giving Doyle £25 for all

rights to the story. The piece appeared later that year in the

Beeton's Christmas Annual and received good reviews in

The Scotsman and the

Glasgow Herald.[5]

The story featured the first appearance of Watson and Sherlock

Holmes, partially modelled after his former university teacher

Joseph Bell. Conan Doyle wrote to him, "It is most certainly

to you that I owe Sherlock Holmes... [R]ound the centre of

deduction and inference and observation which I have heard you

inculcate I have tried to build up a man."[22]

Robert Louis Stevenson was able, even in faraway

Samoa,

to recognise the strong similarity between Joseph Bell and

Sherlock Holmes: "[M]y compliments on your very ingenious and

very interesting adventures of Sherlock Holmes. ... [C]an this

be my old friend Joe Bell?"[23]

Other authors sometimes suggest additional influences—for

instance, the famous

Edgar Allan Poe character

C. Auguste Dupin.[24]

A sequel to

A Study in Scarlet was commissioned and

The Sign of the Four appeared in

Lippincott's Magazine in February 1890, under agreement

with the Ward Lock company. Doyle felt grievously exploited by

Ward Lock as an author new to the publishing world and he left

them.[5]

Short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes were published in the

Strand Magazine. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle first began to

write for the ‘Strand’ from his home at 2 Upper Wimpole Street,

now marked by a memorial plaque.[25]

Sporting

career

While living in

Southsea, Doyle played

football as a goalkeeper for Portsmouth Association Football

Club, an amateur side, under the pseudonym A. C. Smith.[26]

(This club, disbanded in 1896, had no connection with the

present-day

Portsmouth F.C., which was founded in 1898.) Conan Doyle was

also a keen

cricketer, and between 1899 and 1907 he played 10

first-class matches for the

Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC). His highest score, in 1902

against

London County, was 43. He was an occasional bowler who took

just one first-class wicket (although one of high pedigree—it

was

W. G. Grace).[27]

Also a keen golfer, Conan Doyle was elected captain of the

Crowborough Beacon Golf Club,

East Sussex for 1910. He moved to Little Windlesham house in

Crowborough with his second wife Jean Leckie and their family

from 1907 until his death in July 1930.[28]

Marriages and family

In 1885 Conan Doyle married Louisa (or Louise) Hawkins, known

as 'Touie', the sister of one of his patients. She suffered from

tuberculosis and died on 4 July 1906.[29]

The next year he married Jean Elizabeth Leckie, whom he had

first met and fallen in love with in 1897. He had maintained a

platonic relationship with Jean while his first wife was still

alive, out of loyalty to her.[30]

Jean died in London on 27 June 1940.

Conan Doyle fathered five children. He had two with his first

wife: Mary Louise (28 January 1889 – 12 June 1976) and Arthur

Alleyne Kingsley, known as Kingsley (15 November 1892 – 28

October 1918). He also had three with his second wife: Denis

Percy Stewart (17 March 1909 – 9 March 1955) second husband of

Georgian Princess

Nina Mdivani,

Adrian Malcolm (19 November 1910 – 3 June 1970) and

Jean Lena Annette (21 December 1912 – 18 November 1997).[31]

"Death" of Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes statue in Edinburgh, erected

opposite the birthplace of Conan Doyle which was

demolished c.1970

In 1890 Conan Doyle studied ophthalmology in

Vienna, and moved to London, first living in Montague Place

and then in South Norwood. He set up a practice as an

ophthalmologist. He wrote in his autobiography that not a

single patient crossed his door. This gave him more time for

writing, and in November 1891 he wrote to his mother: "I think

of slaying Holmes... and winding him up for good and all. He

takes my mind from better things." His mother responded, "You

won't! You can't! You mustn't!"[32]

In December 1893, in order to dedicate more of his time to

what he considered his more important works (his historical

novels), Conan Doyle had Holmes and

Professor Moriarty apparently plunge to their deaths

together down the

Reichenbach Falls in the story "The

Final Problem". Public outcry, however, led him to bring the

character back in 1901, in

The Hound of the Baskervilles, though this was set at a

time before the Reichenbach incident. In 1903, Conan Doyle

published his first Holmes short story in ten years, "The

Adventure of the Empty House", in which it was explained

that only Moriarty had fallen; but since Holmes had other

dangerous enemies—especially

Colonel Sebastian Moran—he had arranged to also be perceived

as dead. Holmes ultimately was featured in a total of 56

short stories and four Conan Doyle novels, and has since

appeared in

many novels and stories by other authors.

Jane Stanford compares some of Moriarty's characteristics to

those of the

Fenian

John O'Connor Power. 'The Final Problem' was published the

year the Second

Home Rule Bill passed through the House of Commons. 'The

Valley of Fear' was serialised in 1914, the year, Home Rule, The

Government of Ireland Act (Sept.18) was placed on the Statute

Book.[33]

Political campaigning

Following the

Boer War in South Africa at the turn of the 20th century and

the condemnation from around the world over the United Kingdom's

conduct, Conan Doyle wrote a short work titled The War in

South Africa: Its Cause and Conduct, which justified the

UK's role in the Boer War and was widely translated. Doyle had

served as a volunteer doctor in the Langman Field Hospital at

Bloemfontein between March and June 1900.[34]

Conan Doyle believed it was this publication that resulted in

his being

knighted by

King Edward VII in 1902[16]

and appointed a Deputy-Lieutenant of

Surrey.[35]

Also in 1900 he wrote a book,

The Great Boer War. During the early years of the 20th

century, he twice stood for Parliament as a

Liberal Unionist—once in Edinburgh and once in the

Hawick Burghs—but although he received a respectable vote,

he was not elected.

Conan Doyle was a supporter of the campaign for the reform of

the

Congo Free State, led by the journalist

E. D. Morel and the diplomat

Roger Casement. During 1909 he wrote The Crime of the

Congo, a long pamphlet in which he denounced the horrors of

that colony. He became acquainted with Morel and Casement, and

it is possible that, together with

Bertram Fletcher Robinson, they inspired several characters

in the 1912 novel

The Lost World.[36]

However, Doyle broke with both Morel and Casement when Morel

became one of the leaders of the

pacifist movement during the

First World War. When Casement was found guilty of

treason against

the Crown during the

Easter Rising, Doyle tried unsuccessfully to save him from

facing the death penalty, arguing that Casement had been driven

mad and could not be held responsible for his actions.

Correcting injustice

Conan Doyle was also a fervent advocate of justice and

personally investigated two closed cases, which led to two men

being exonerated of the crimes of which they were accused. The

first case, in 1906, involved a shy half-British, half-Indian

lawyer named

George Edalji who had allegedly penned threatening letters

and mutilated animals. Police were set on Edalji's conviction,

even though the mutilations continued after their suspect was

jailed.

It was partially as a result of this case that the

Court of Criminal Appeal was established in 1907, so not

only did Conan Doyle help George Edalji, his work helped

establish a way to correct other miscarriages of justice. The

story of Conan Doyle and Edalji was fictionalised in

Julian Barnes's 2005 novel

Arthur & George and dramatized in an episode of the 1972

BBC television series, "The Edwardians". In Nicholas Meyer's

pastiche

The West End Horror (1976), Holmes manages to help clear

the name of a shy

Parsee Indian character wronged by the English justice

system. Edalji himself was of Parsee heritage on his father's

side.

The second case, that of

Oscar Slater, a German Jew and gambling-den operator

convicted of bludgeoning an 82-year-old woman in

Glasgow in 1908, excited Conan Doyle's curiosity because of

inconsistencies in the prosecution case and a general sense that

Slater was not guilty. He ended up paying most of the costs for

Slater's successful appeal in 1928.[37]

Spiritualism

One of the five photographs of Frances Griffiths

with the alleged fairies, taken by Elsie Wright in

July 1917

Following the death of his wife Louisa in 1906, the death of

his son Kingsley just before the end of

World War I, and the deaths of his brother Innes, his two

brothers-in-law (one of whom was

E. W. Hornung, creator of the literary character

Raffles) and his two nephews shortly after the war, Conan

Doyle sank into depression. He found solace supporting

spiritualism and its attempts to find proof of existence

beyond the grave. In particular, according to some,[38]

he favoured

Christian Spiritualism and encouraged the

Spiritualists' National Union to accept an eighth precept –

that of following the teachings and example of

Jesus

of Nazareth. He also was a member of the renowned

supernatural organisation

The Ghost Club.[39]

Its focus, then and now, is on the scientific study of alleged

supernatural activities in order to prove (or refute) the

existence of supernatural phenomena.

On 28 October 1918 Kingsley Doyle died from pneumonia, which

he contracted during his convalescence after being seriously

wounded during the 1916

Battle of the Somme. Brigadier-General Innes Doyle died,

also from pneumonia, in February 1919. Sir Arthur became

involved with Spiritualism to the extent that he wrote a

Professor Challenger novel on the subject,

The Land of Mist.

His book The Coming of the Fairies (1922)[40]

shows he was apparently convinced of the veracity of the five

Cottingley Fairies photographs (which decades later were

exposed as a hoax). He reproduced them in the book, together

with theories about the nature and existence of fairies and

spirits. In The History of Spiritualism (1926), Conan

Doyle praised the

psychic phenomena and spirit materialisations produced by

Eusapia Palladino and

Mina "Margery" Crandon.[41]

Conan Doyle with his family in New York City, 1922

Conan Doyle was friends for a time with

Harry Houdini, the American magician who himself became a

prominent opponent of the Spiritualist movement in the 1920s

following the death of his beloved mother. Although Houdini

insisted that Spiritualist mediums employed trickery (and

consistently exposed them as frauds), Conan Doyle became

convinced that Houdini himself possessed supernatural powers—a

view expressed in Conan Doyle's The Edge of the Unknown.

Houdini was apparently unable to convince Conan Doyle that his

feats were simply illusions, leading to a bitter public falling

out between the two.[41]

In 1920 Doyle debated the notable skeptic

Joseph McCabe on the claims of

Spiritualism at Queen's Hall in London. McCabe later

published his evidence against Doyle and Spiritualism in a

booklet entitled Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud? which

claimed Doyle had been duped into believing Spiritualism by

mediumship trickery.[42]

Richard Milner, an American historian of science, has

presented a case that Conan Doyle may have been the perpetrator

of the

Piltdown Man hoax of 1912, creating the counterfeit

hominid

fossil that fooled the scientific world for over 40 years.

Milner says that Conan Doyle had a motive—namely, revenge on the

scientific establishment for debunking one of his favourite

psychics—and that

The Lost World contains several encrypted clues

regarding his involvement in the hoax.[43][44]

Samuel Rosenberg's 1974 book

Naked is the Best Disguise purports to explain how,

throughout his writings, Conan Doyle left open clues that

related to hidden and suppressed aspects of his mentality.

In 1970, a woman identified only as Vera claimed that she had

transcribed works via her dead mother from numerous deceased

authors including Conan Doyle. Vera's father, a retired 73

year-old bank officer only identified as "Mr. A" submitted the

material - a collection entitled

Tales of Mystery and Imagination - to author

Peter Fleming who dismissed it as "tosh". Author

Duff Hart-Davis noted that the work was "crude, devoid of

literary merit, and all almost exactly the same" despite

allegedly being the work of numerous authors.[45]

Death

Grave of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at

Minstead, England

Conan Doyle was found clutching his chest in the hall of

Windlesham Manor, his house in

Crowborough, East Sussex, on 7 July 1930. He died of a heart

attack at the age of 71. His last words were directed toward his

wife: "You are wonderful."[46]

At the time of his death, there was some controversy concerning

his burial place, as he was avowedly not a Christian,

considering himself a Spiritualist. He was first buried on 11

July 1930 in Windlesham rose garden. He was later reinterred

together with his wife in

Minstead churchyard in the New Forest, Hampshire.[5]

Carved wooden tablets to his memory and to the memory of his

wife are held privately and are inaccessible to the public. That

inscription reads, "Blade straight / Steel true / Arthur Conan

Doyle / Born May 22nd 1859 / Passed On 7th July 1930." The

epitaph on his gravestone in the churchyard reads, in part:

"Steel true/Blade straight/Arthur Conan Doyle/Knight/Patriot,

Physician, and man of letters".[47]

Undershaw, the home near

Hindhead,

Haslemere, south of London, that Arthur Conan Doyle had

built and lived in between October 1897 and September 1907,[48]

was a hotel and restaurant from 1924 until 2004. It was then

bought by a developer and stood empty while conservationists and

Conan Doyle fans fought to preserve it.[29]

In 2012 the High Court ruled that the redevelopment permission

be quashed because proper procedure had not been followed.[49]

A statue honours Conan Doyle at Crowborough Cross in

Crowborough, where he lived for 23 years.[50]

There is also a statue of Sherlock Holmes in Picardy Place,

Edinburgh, close to the house where Conan Doyle was born.[51]

Bibliography

See also

References

-

^ "Conan

Doyle Dead From Heart Attack",

New York Times, 8 July 1930. Retrieved 4

November 2010.

-

^

"Scottish writer best known for his creation of the

detective Sherlock Holmes". Encyclopaedia

Britannica.

Retrieved 30 December 2009.

-

^

"Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Biography".

sherlockholmesonline.org.

Archived from the original on 2 February 2011.

Retrieved 13 January 2011.

-

^ The

details of the births of Arthur and his siblings are

unclear. Some sources say there were nine children, some

say ten. It seems three died in childhood. See Owen

Dudley Edwards, "Doyle, Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan

(1859–1930)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,

Oxford University Press, 2004;

Encyclopaedia Britannica; Arthur Conan

Doyle: A Life in Letters, Wordsworth Editions, 2007

p. viii.

ISBN 978-1-84022-570-9

-

^

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

j

k

Owen Dudley Edwards,

"Doyle, Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan (1859–1930)",

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford

University Press, 2004

-

^

Golgotha Pres (2011). The

Life and Times of Arthur Conan Doyle. BookCaps Study

Guides.

ISBN 9781621070276.

"In time, he would reject the Catholic religion and

become an agnostic."

-

^

Brown, Yoland (1988).

Ruyton XI Towns, Unusual Name, Unusual History.

Brewin Books. pp. 92–93.

ISBN 0-947731-41-5.

-

^ Stashower

30–31.

-

^ Conan

Doyle, Arthur (Author), Lellenberg, Jon (Editor),

Stashower, Daniel (Editor) (2012). Dangerous Work:

Diary of an Arctic Adventure. Chicago: University Of

Chicago Press.

ISBN 022600905X .

ISBN 978-0226009056.

-

^ Available

at the

Edinburgh Research Archive.

-

^

Lellenberg, Jon; Daniel

Stashower and Charles Foley (2007). Arthur Conan

Doyle: A Life in Letters. HarperPress. pp. 8–9.

ISBN 978-0-00-724759-2.

-

^

Stashower, Daniel (2000).

Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle.

Penguin Books. pp. 20–21.

ISBN 0-8050-5074-4.

-

^ Stashower

says that the compound version of his surname originated

from his great-uncle Michael Conan, a distinguished

journalist, from whom Arthur and his elder sister,

Annette, received the compound surname of "Conan Doyle"

(Stashower 20–21). The same source points out that in

1885 he was describing himself on the brass nameplate

outside his house, and on his doctoral thesis, as "A.

Conan Doyle". However, the 1901 census indicates that

Conan Doyle's surname was "Doyle", leading some sources

to assert that the form "Conan Doyle" was used as a

surname only in his later years.[citation

needed]

-

^

Christopher Redmond, Sherlock Holmes Handbook

(Dundurn, 2nd edition 2009),

p. 97

-

^ Steven

Doyle & David A. Crowder, Sherlock Holmes for Dummies

(Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010),

p. 51

-

^

a

b

The London Gazette:

no. 27494. p. 7165. 11 November 1902.

Retrieved 28 May 2013.

-

^ Cutis,

vols. 53-54 (1994), p. 312: "A large stone cross stands

over a simple half-oval white stone, inscribed: "Steel

True, Blade Straight, Arthur Conan Doyle, Knight,

Patriot, Physician & Man of Letters, 22 May 1859 - 7

July 1930, And His Beloved, His Wife, Jean Conan

Doyle..."

-

^ Stashower

52–59.

-

^

UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available

from Lawrence H. Officer (2010) "What

Were the UK Earnings and Prices Then?"

MeasuringWorth.

-

^ Stashower

55, 58–59.

-

^

Saunders, Emma (6 June 2011).

"First Conan Doyle novel to be published". BBC.

Archived from the original on 7 June 2011.

Retrieved 6 June 2011.

-

^

Independent, 7 August 2006.

-

^ Letter

from R L Stevenson to Conan Doyle 5 April 1893

The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson Volume 2/Chapter

XII.

-

^ Sova, Dawn

B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark

Books, 2001. pp. 162–163.

ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

-

^ City of

Westminster green plaques

http://www.westminster.gov.uk/services/leisureandculture/greenplaques/

-

^

Juson, Dave; Bull, David

(2001). Full-Time at The Dell.

Hagiology. p. 21.

ISBN 0-9534474-2-1.

-

^

"London County v Marylebone Cricket Club at Crystal

Palace Park, 23–25 Aug 1900". Static.cricinfo.com.

Retrieved 2 March 2010.

-

^ Arthur

Conan Doyle. "Memories and Adventures". p. 222. Oxford

University Press, 2012

-

^

a

b

Leeman, Sue, "Sherlock

Holmes fans hope to save Conan Doyle's house from

developers", Associated Press, 28 July 2006.

-

^ Janet B.

Pascal (2000). "Arthur Conan Doyle:Beyond Baker Street:

Beyond Baker Street". p. 95. Oxford University Press

-

^

"Obituary: Air Commandant Dame Jean Conan Doyle".

The Independent. Retrieved 6 November 2012

-

^

Panek, LeRoy Lad (1987).

An Introduction to the Detective Story.

Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University

Popular Press. p. 78.

ISBN 0-87972-377-7.

Retrieved 4 January 2012.

-

^ Stanford

Jane, 'That Irishman: The Life and Times of John

O'Connor Power', pp. 30, 124-127, History Press Ireland,

May 2011,

ISBN 978-1-84588-698-1

-

^ Miller,

Russell. The Adventures of Arthur Conan Doyle.

New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2008. pp. 211–217.

ISBN 0-312-37897-1.

-

^

The London Gazette:

no. 27453. p. 4444. 11 July 1902. Retrieved

28 May 2013.

-

^

Spiring, Paul.

"B. Fletcher Robinson & 'The Lost World'".

Bfronline.biz.

Retrieved 2 October 2011.

-

^

Roughead, William (1941). "Oscar Slater". In Hodge,

Harry. Famous Trials 1. Penguin Books.

p. 108.

-

^

Price, Leslie (2010).

"Did Conan Doyle Go Too Far?". Psychic News

(4037).

-

^

Ian Topham (2010-10-31).

"The Ghost Club - A History by Peter Underwood |

Mysterious Britain & Ireland".

Mysteriousbritain.co.uk.

Retrieved 2013-05-28.

-

^

"The coming of the fairies / by Arthur Conan Doyle".

British Library catalogue.

British Library.

Retrieved 12 June 2013.

-

^

a

b

Kalush, William, and Larry

Sloman, The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of

America's First Superhero, Atria Books, 2006.

ISBN 0-7432-7207-2.

-

^

Joseph McCabe. (1920).

Is Spiritualism Based On Fraud? The Evidence Given By

Sir A. C. Doyle and Others Drastically Examined.

London Watts & Co.

-

^

"Piltdown Man: Britain's Greatest Hoax" 17 February 2011

BBC

-

^

"Piltdown Man: British archaeology's greatest hoax"

The Guardian 5 February 2012

-

^

Hart-Davis, Duff (1974). Peter Fleming: A

Biography. London:

Jonathan Cape. pp. 388–393.

ISBN 0-224-01028-X.

The other authors include

Ian Fleming,

H. G. Wells,

Edgar Wallace,

Ruby M. Ayres,

W. Somerset Maugham and

George Bernard Shaw.

-

^ Stashower,

p. 439.

-

^ Johnson,

Roy (1992). "Studying Fiction: A Guide and Study

Programme". p.15. Manchester University Press

-

^

Duncan, Alistair (2011).

An Entirely New Country: Arthur Conan Doyle, Undershaw

and the Resurrection of Sherlock Holmes. MX

Publishing.

ISBN 978-1908218193.

-

^

"Sir Arthur Conan Doyle house development appeal upheld".

BBC News. 12 November 2012.

Retrieved 12 November 2012.

-

^

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930), (Author database)

www.librarything.com. Retrieved: 17 March 2012.

-

^

"Sherlock Holmes statue reinstated in Edinburgh after

tram works", BBC. Retrieved 6 November 2012

External links

|

|

|

1)

scrivi

le parole inglesi dentro la

striscia gialla

2)

seleziona il testo

3)

clicca "Ascolta il testo"

DA INGLESE A ITALIANO

Inserire

nella casella Traduci la parola

INGLESE e cliccare

Go.

DA ITALIANO A INGLESE

Impostare INGLESE anziché italiano e

ripetere la procedura descritta.

|

|